Degrees of Seperation within Wikipedia: How Many Click's Till the Homunculus?

Thinking about small-world phenomena in information networks, this post looks at the degrees of separation between Wikipedia articles. Using the article “Homunculus” as central node it will ask how closely linked seeming disparate topics can be.

Sensory Homunculi trying to connect on big and small worlds whilst Adam Sandler and others Click. 2017.

Sensory Homunculi trying to connect on big and small worlds whilst Adam Sandler and others Click. 2017.

Six Degrees of Separation…?

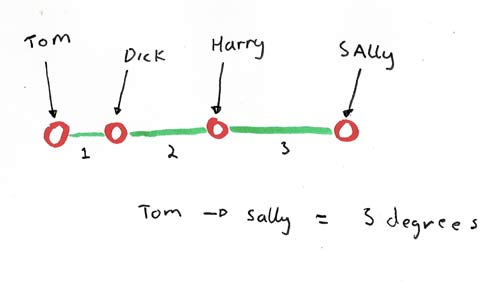

You might have heard the expression that there are six degrees of separation between everyone on the planet. This describes the hypothesis that if you were to make a chain between the right mutual friends, it would take 6 connections to reach anyone. Though this figure might not be completely accurate, it expresses what has been called the small-world phenomenon.

Simple description of degrees of separation just so I know we are on the same page.

Simple description of degrees of separation just so I know we are on the same page.

Though originally the term might have belonged more to anecdotal folklore than any kind of empirical analysis, it has been found to be quite descriptive of certain types of networks. Stanley Milgram’s experimental study in the 1960’s was one of the first to quantify this phenomenon and is probably still the most famous. Its participants were instructed to send a letter to a randomly selected person in their country, if they didn’t know them they were to send their letter to someone they thought more likely to, the next person would then repeat the same steps until the target was reached. This process of posting chain letters found, on average, 6 steps between any 2 people in the United States. More recently Facebook did an analysis of its own social network finding the average separation between any of it 1.59 billion active users was 3.57 – Something that fits in quite nicely with the rhetoric of making the world more connected.

Another interesting point noted about the Milgram experiment was not just the degree of separation between people, but also, that equipped only with their own local knowledge, each were collectively able to reach their target in so few steps. As Jon Kleinberg has shown, these types of networks can be navigated efficiently through decentralised search algorithms – something humans seem to be quite good at IRL.

Though some of this might be surprising, research done by Duncan Watts and Steven Strogatz have pointed out a wide variety of types of graphs exhibit small world properties (high clustering and a small diameter). These have included: the structure of the internet, neurons in brains, gene pools, and what we will be focusing on here encyclopaedia formats such as Wikipedia.

Connecting Information Within Wikipedia

If you haven’t played the Wikipedia game before, it probably worth a go. Though there are few variations, the general aim is to get from one randomly selected article to another using only the links within each article and in the fewest possible steps. Without being allowed to use the back button or any other navigational tools the real trick is finding right links that will get you closer to your target. In the same way as degrees of separation were made between people by friendships, here edges between nodes are made by the literal hyperlinks between them.

As a small experiment, I wanted to get a feel of the paths between these articles for myself. Though there were some instances of this online, I didn’t feel like it was hands on enough for me and to be honest, I thought the process would be a good learning experience. This investigation aimed to find the shortest paths between a sample set all directed to the article about homunculi. Though the ‘Homunculus’ article was chosen rather arbitrarily, it was hoped it would be representative of a pretty average Wikipedia page in terms of its number of inbound and outbound links.

Trying to find the shortest path between two pages (the least amount of links visited between them), without taking the time to find a good heuristic or weighting policy, I pretty much had to do something like getting the computer to visit all the links, on all the pages, between all start and end points. Though this is a relatively simple process it can still be extremely slow even for a computer as the search space gets very large very quickly. Say for instance every page we visit only has 20 links on it we only have got to go 4 cycles deep to have visited around 160,000 articles. With there being around 5.5 million English Wikipedia articles at the time of writing this, with only a small laptop and a bad internet connection I’m happy with a moderate estimate. In the end, I used a memoizing bidirectional search over the Wikimedia API to get the results. Though it may produce some slightly sub-optimal paths, it’s a worthwhile compromise. The Python code used and data collected can be found on GitHub.

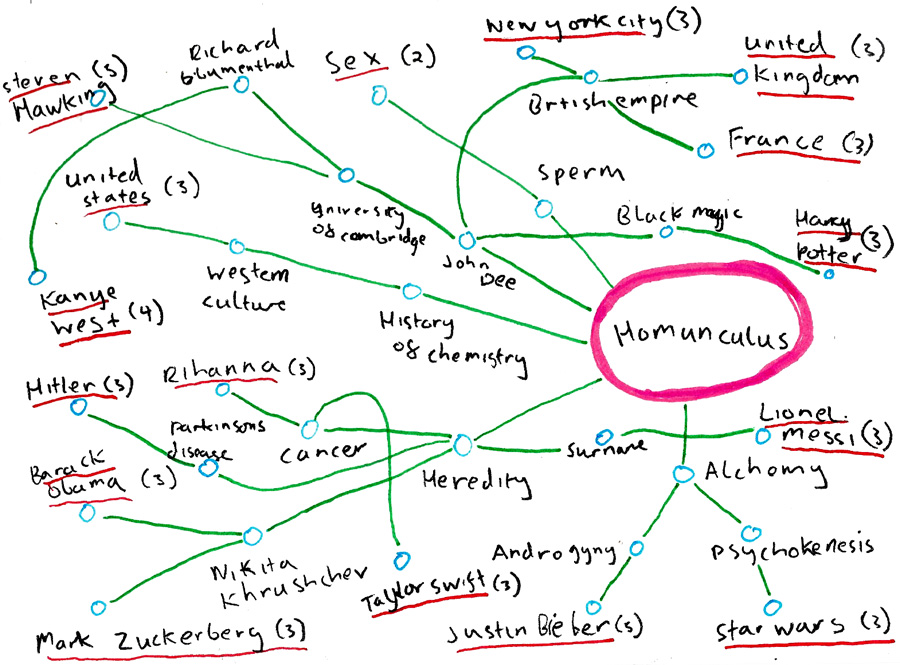

Search Results

From a search sample from 500 random pages (rand500) it took an average 3.92 clicks to get to the homunculus article. From another sample containing the 50 most visited articles (top50) this number drops to 3.02. Here is a sketch of some of the shortest paths within top50 so you can get an idea of what some of the connections are. The starting points are underlined in red and their path lengths are bracketed beside these titles.

Bad drawing of paths to the 'Homunculus' Wikipedia article from an arbitary selection of the top most visited wikipedia articles.

Bad drawing of paths to the 'Homunculus' Wikipedia article from an arbitary selection of the top most visited wikipedia articles.

Using the indegree of each starting position, we can see how the ‘Homunculus’ article compares in terms of the number of links pointing to it. The mean indegree across the samples where as follows: rand500=65.43, top50=47,300.40. The indegree of ‘Homunculus’ was 223.00, the min was 0.00 and the max across all samples was the ‘United States’ which had a massive 462,672.00 links pointing to it.

From within the top 50 most visited articles (top50), it seems countries generally had more links pointing to them than other genres. In trying see how the ‘Homunculus’ article compares to the rest of Wikipedia, conclusions cannot be made without more data, especially due to the massive inconsistencies across the samples here. More notes can be found on github at this Jupyter notebook.

Trying to compare these results with the investigations of others, it was hard to find any recent definitive answers. An analysis of the whole site downloaded in 2008 found 4.57 clicks to get from any article to any other and from the then most central article (‘2007’) only 3.45 clicks. Given that the number of Wikipedia articles has doubled since then but the amount of total article text content has tripled, richer amount of content per article could have resulted in more links and a shorter average distance between articles. Another study that used different techiques and removed the articles with more than 500 links found around 5 links between articles. What the exact distance is, I guess doesn’t matter, what does matter is that we know it is generally quite short.

Conclusion

Considering this has been small DIY experiment with limited resources, it has been quite insightful, for myself at least. As has been shown here, many Wikipedia articles are more closely linked that you may have initially thought. However, simply knowing that possibly valuable information within these networks is only a few clicks away, although interesting, doesn’t help you find it. Beyond navigation, questions arise around the reliability, accessibility and completeness of information within Wikipedia. These make for curious and divergent investigations which may be considered here amongst future articles.