Contemporary Citizenship

In-order to contextualise future investigations, a reasonable starting point for a blog entitled ‘Digital citizens’ would be to first establish some definitions of citizenship. This will be discussed in relation to more classical considerations before considering the impacts of the internet, and digital cultures.

Introduction to Citizenship

Looking for a normative definition of citizenship, even when limiting discussions to liberal western democracies, one finds a varied and contested debate. As with all normative theories, we are discussing idealised situations. That is, conceived standards of what citizenship should be, not exactly how it is. To many, the procurement of so called good citizenship has become to symbolise a cure to all apparent dysfunction within democracies (Bellamy, R. 2008. pp.1-2).

Classical discourse: Liberal vs Republican

Discussions of citizenship can be split broadly into two major points of reference. These can be defined as the liberal or republican models (Leydet, D. 2017). Though In practice, civil societies require consideration of each model, discursively is preferable to provide this distinction to clarify what dimensions of citizenship are being explored (Kymlicka, W. and Norman, W. 1994).

The liberal model is most concerned with the entitlements to certain civil, political and legal rights that come from membership to specific political communities. These entitlements are often nationally sovereign or given by some supra-national entity, for example in the European Union, citizens are protected by its European Convention of Human Rights. This also discussed as an idea of ‘citizenship-as-legal status’ (Kymlicka, W. and Norman, W. 1994. p.353), the legal-judiciary sense of citizenship or generally the ‘right to have rights’.

The republican model, that which can be similarly characterised as ‘citizenship-as-desirable-activity’ (Kymlicka, W. and Norman, W. 1994. p.353), explores the duties and responsibilities that are expected from citizens. This often includes the understanding of relevant democratic processes and generally playing an active part within the political community. For example, here we could be discussing the duty of citizen’s to be knowledgeable of political system they inhabit in order the render them capable of rational informed choice.

Taken individually each model may neglect certain aspects required for so called high-functioning’ democracies (Kymlicka, W. and Norman, W. 1994). Sole concentration on the right to have rights disregards the responsibilities and active participation of citizens. Participation is argued as positive as it can foster a sense of community and purposefulness, essentially that their voice matters. Legal rights in many cases underpin the participation the republican model aspires. For instance, proper public deliberation requires there be something like the U.S constitution’s First Amendment as an enabler of citizens to assemble and speak freely. Without a strong legal framework that establishes the conditions of civil and political rights there is no expressed assurance of individual’s equal opportunity to participate fully within the society. Though as history shows us this is not necessarily the case.

Citizenship and Social Class

A seminal thesis on the rights of citizens can be seen in T.H. Marshall’s, ‘Citizenship and Social class’. Informed by the sensibilities of the post war era, Marshall sought to establish the need for certain civil, political and social rights that guaranteed access to an established shared standard of living for all within the community (1950). The embodiment of this theory in public policy ultimately equates to the existence of a welfare state.

Though an egalitarian ideal that has provided many benefits, this universalist approach has faced criticism for failing to fully accommodate for the unequal needs of modern pluralistic societies (Leydet, D. 2017).

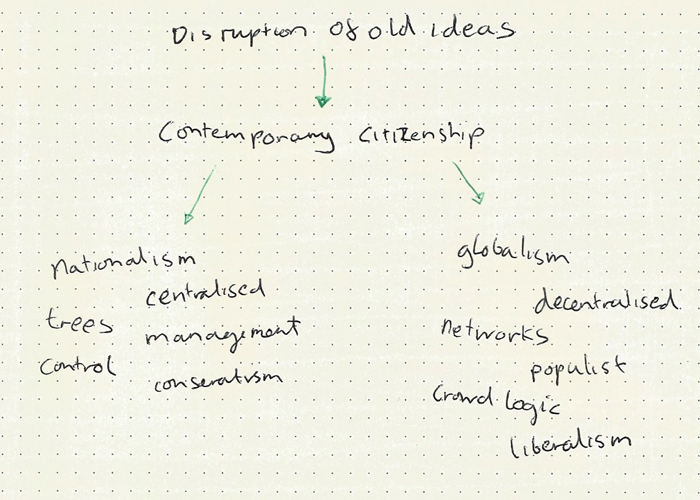

Global and national divides

So far, conceptions of citizenship discussed here are rooted in sovereign states, belonging to specific geographically based communities that generally pertain a cohesive cultural identity. Globalisation has provided several challenges that have forced a re-evaluation on what the preconditions of citizenship should entail. This had led to polarising cultural conflicts between nationalist and post-nationalist ideologies. Some common lines of these divides could be annotated as follows:

(TODO: maybe more here, (democratic citizenship))

Digital citizenship

Here comes the Internet

Especially in relation to the internet, new communication technologies have often invoked utopian ideas that have had both their supporters and detractors. Jon Perry Barlow’s declaration of cyberspace is perhaps a reminder of how far these visons go. Its talk of creating a ‘civilization of the Mind in Cyberspace’, free from past governmental constraints, though maybe inspiring seems naïve considering the present situation.

(TODO: wtf the present)

Ideas of digital citizenship

Karen Mossberger defines ‘digital citizenship’ as ‘the ability to participate in in society online’ (Mossberger, K. et al. 2007. p.1). Her position goes beyond mere access to include the sufficient technological literacy to fulfil their duties as contemporary citizens. The main persuasion of their book (‘Digital citizenship’), which they back up with several studies, is that engaging regularly online brings a range of civic and economic benefits. Mossberger and co-authors cite an interesting quote T.H. Marshall in positioning their normative ideal.

‘Societies in which citizenship is a developing institution create and image of an ideal citizenship against which achievement can be measured and towards which aspiration can be directed.’ (T.H. Marshall. 1949; cited in Mossberger, K. et al. 2007. p.139)

Using this they go on to position that digital citizenship is ‘the ideal of citizenship in the 21st century’ (p.140). Though they make a reference to an individual who uses technology regularly in a political self-empowering manner, we could still go further and ask well what is the ideal digital citizen? How much technological know-how do they need? Is it enough to just engage with political content and discussion? There obviously needs to be some ability to differentiate the validity of information sources. Do these discussions need to be rational, like deliberative theory often emphasises. What about cyber security? Is the better citizen the one with the stronger password more layers of account authentication? Do they need to make sure their windows computer is up to date?

(TODO: sort this out a bit)

Preconditions for good citizenship

Steven Coleman describes four capabilities he perceives to be required for citizens to be ‘autonomous, informed, reflective efficacious social actors’. Though not a conclusive blueprint for a stronger democracy, they highlight issues especially relevant to technology.

- Being able to make sense of the political world. – can experience be openly circulated? Do citizens have sufficient access to reliable information?

- Being open to argumentative exchange – is the space for divergent ideas to interact? Are these encounters able to change opinions?

- Being recognised as someone who counts.

- Being able to make a difference. – Is there confidence in the authorities ability to execute their wishes? Is there equal access?

(TODO: ???)

Conclusion

This has obviously not been a complete introduction to literature concerning citizenship nor its relation to digital technologies, this would be far to encompassing for a single blog post. It has however tried to position concepts that may be of interest later within this project. These will be used going forward whilst also introducing new ideas.

References:

- Bellamy, R. 2008. Citizenship: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, UK. Oxford University Press.

- Coleman, S. and Blumler, J. 2009. The Internet and Democratic Citizenship: Theory, Practice and Policy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dahlberg, L. 2001. The internet and Democratic Discourse: Exploring the Prospects of Online Deliberative Forums Extending the Public Sphere. Information, Communication & Society. [Online]. 4(4), pp. 616-663. [Accessed 3 January 2018]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180110097030

- Dahlgren, P. 2005. The Internet, Public Spheres, and Political Communication: Dispersion and Deliberation. Political Communication. [Online]. 22(2), pp.147-162. [Accessed 3 January 2018]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600590933160

- Kymlicka, W. and Norman, W. 1994. Return of the Citizen: A Survey of Recent Work on Citizenship Theory. Ethics. [Online]. 104(2), pp. 352-381. [Accessed 3 January 2018]. Available from: www.jstor.org/stable/2381582

- Marshall T.H. 1950. Citizenship and Social Class: and Other essays. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. Available from: http://www.jura.uni-bielefeld.de

- Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C.J. and McNeal, R.S. 2007. Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society, and Participation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Leydet, D. 2017. Citizenship. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu