Data, politics and democracy part 4: Reflections

Investigations here have predominantly focused on what has been shared, not how, or by which individuals specifically. This is translated into analysis of both the initial news coverage from the Guardian and the posts made via Twitter. Now this event in will be discussed in relation theories on digital privacy, also reviewing the regulatory conditions for Facebook and the underlying logic of web 2.0. It will finish by assessing some normative implications for democracies and the roles different forms of media play in addressing such issues.

Privacy Paradox?

It’s clear from both the news coverage and data collected here, that there was an apparent breach of trust in how data was shared, and through such strategies such as #deleteFacebook, users sought to express this. What is less clear is how much of an effect this has had on both long-term privacy attitudes and whether or not this incident will lead to any meaningful actions by either Facebook users or the site itself.

Privacy attitudes

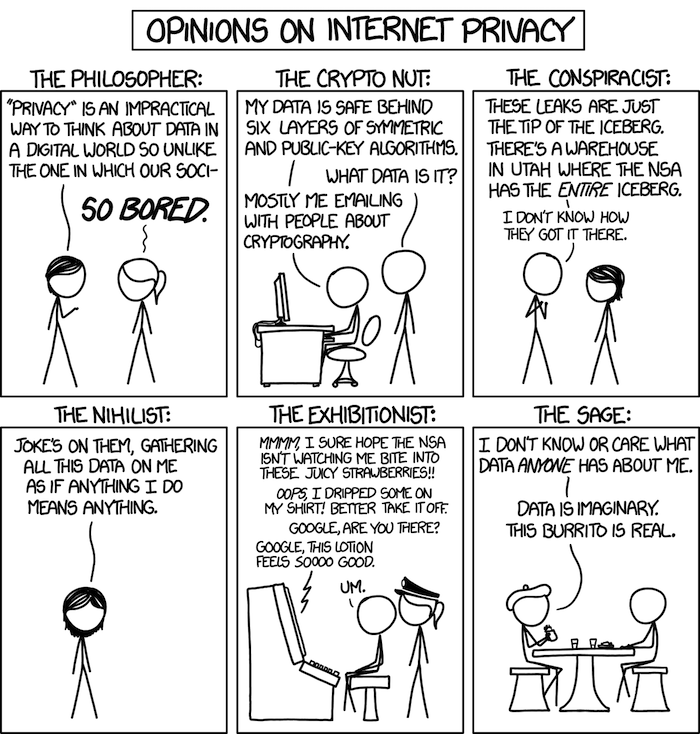

Looking at what people say about their privacy and what they in actually do, often doesn’t add up. The privacy paradox describes the disconnect between people’s willingness to disclose personal information online given the levels of concern they express (Young, A. and Quan-Haase, A. 2013. p.479). Generally, people say they value things like privacy, freedom, and security but despite this, there are many situations which they are willing to waver certain rights in varying forms of exchange. These rights are at times negotiated, at other eroded by changes by societal norms, or personal omissions given more tacitly.

A longitudinal study examining privacy attitudes and self-disclosure patterns of Facebook users over the last 5 years, found that although ‘heavy users’ had seen a marked increase in concern, the opinions of ‘light users’ has remained approximately the same (Tsay-Vogel, M., Shanahan, J. and. Signorielli, N. 2018). Not only that, but increases in concerns seem to be plateauing for heavy users. Authors have argued that this supports the hypothesis that the ongoing exposure and habitual nature of social media use has effected perceptions not only what levels of self-disclosure are normal, but what is expected.

Sharing in changing contexts

Despite this, studies have also shown that individuals do take active steps to negotiate their privacy within the constraints of Facebooks available settings (Marwick, A. and Boyd, D. 2014; Young, A. and Quan-Haase, A. 2013). As a prerequisite, Facebook requires users to share at least some information for them to connect with other users. Helen Nissenbaum describes the importance of the context in which information Is disclosed, essentially that privacy strategies should be coherent to and informed by the conditions in which data was indented to be used (2010). As discussed in part 2 of this series, Facebook’s default settings dictate that most posted information is shared between ‘friends’, which to a large extent sets the tone of social exchange. Through tacit knowledge it is understood that their information is correspondingly used by Facebook as it sees fit, by personalising content, selling adds etc. It is in this context that privacy is negotiated, not only between general end users but equally developers, advertisers and within company itself. Given this, it is not surprising that there are disjunctions perceived acceptable standards.

To place this issue fully, privacy considerations need to consider the scope and topology of how data flows. The idea of networked privacy, gives the recognition that information is often intertwined within relationships of users making it difficult for individuals to fully negotiate how information may be shared (Marwick, A. and Boyd, D. 2014). This was explicit within this scandal as the original dataset collected by Aleksandr Kogan relied on the prior relaxed conditions that enabled Facebook users to share the personal data of all their friends through taking an online survey. Naturally, one could not argue that any of them would have predicted where this data would end up, especially using technology that didn’t then exist. Marwick and Boyd argue that these changing and co-constructed contexts that are framed by networked privacy can collapse the rules of contextual integrity that Nissenbaum describes (2014. pp.1063-1064). As context is interpretable in several ways, understanding initial consent once data has been exchanged multiple times loses its meaning.

Established concerns

Establishing privacy online as a paradox doesn’t offer explanation to the contradictions it claims. As has been discussed, individuals take active steps to mitigate data collection and though the increases in the levels of concern are stagnating, apprehension very much exists. Positioning the Cambridge Analytica scandal against the background of stories on privacy over the last 8 years (part 3: fig 5), the Idea that varying institutions are gathering large amounts of data on them is not something that is alien to citizens. While the Guardian is typically addressing a specific kind of left leaning reader, these stories often have led to wide spread coverage across differing media. Some people may not be concerned with their privacy; however, the overall picture is of greater sustenance to its related issues in social and broadcast media.

The regulation of and by Facebook

Literature written by Tarleton Gillespie has recently considered the ‘regulation of and by platforms’ (2018), in particular considering how user generated content is managed. With reference to Section 230 of the US’s Communication Decency Act (1996), an argument is made that current content regulation, whilst protecting social media providers was instead designed for Internet service providers and search engines (pp.255-260). Stating the impossibility of platform impartiality, an emphasis is placed on importance of their own governance and curation online spaces (p.262). Regulations for tech companies are outdated, ill-suited and sometimes non-existent with respect to contemporary concerns. Be it the beta testing of self-driving cars on public roads, deciding how data is collected and sold, and the negotiations of speech limitations within platforms, the underlying theme expressed by law, particularly in the US, is that tech companies can just regulate themselves and innovation should not be stifled. The issue raised in this scandal concerns both the regulation of data and content produced for political contexts along with their underlying strategies.

Political regulation

With the implementation of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR), for European users at least, Facebook will supposedly have to uphold the new standards presented. This includes; attempts to make terms and conditions more transparent, the right to be forgotten, rights to access data concerning themselves and several other safeguards for citizens [ref. Though Facebook claims to be on board with the regulation, reports claim the company is shifting the data of over a billion users to more liberal regulatory environments. This is obviously counter evidence to their claims.

Self-regulation

Even without intervention by political institutions, Facebook has strong incentives to adapt their policies to meet user preferences. As Gillespie also notes, even with their level of monopolisation, companies like Facebook still don’t want to lose large numbers of users to competitors (2018, p.262). To do this it needs to keep the users happy. The trouble it is not just the end users that it needs to satisfy.

In analysing Facebooks attitude to regulation, it is important to take note of the multitude of actors it is aiming to satisfy. Bucher and Helmond (2018) bring consideration to the affordances of social media platforms in relation to their different types of consumers; Including advertisers, investors, end users, developers, and the platforms themselves. Looking to a variety of definitions of affordance, they emphasise the inherent reciprocity that is involved – that is, not just what technology affords users but equally what users afford technology. In Facebook, an obvious example of this would be through user actions providing data points for the sites personalisation algorithms. Throughout Facebook trying to satisfy the combination of its ethos, end users, developers, advertisers and investors, conflicts have naturally arisen. Facebook may want users feel their data is shared minimally, whilst to advertisers they might wish assure that maximum access is granted. Users themselves may also be in conflict with their relationship to data practices; they might not want to share their data but contrastingly prefer more personalised content.

Democratic Governance

Though Facebook may have enjoyed praise for their apparent democratising potential (e.g. superficially, the Arab Spring), the plight of claims for facilitating fake news, political polarisation, this scandal, and their apparent failure to take meaningful responsibility, has led to discontentment in users, politicians and investors alike. Facebook is a place where a combination of public, private and corporate interests competes for the social and connective assets that the site commands (Van Dijck, J. 2012). The problems of this online space reflect the issues faced by democracies in general. Could democratic input from users produce an environment of greater accountability and increased satisfaction? Well it turns out 2009 Mark of 200 million users thought so…

Reportedly, the experiment didn’t work out, though it’s not sure it can be said they tried. The company sites low turnout but critics have argued that users were only given a limited choice of two slightly different terms of service, not how the company was structurally run.

Standards for democracy

A key argument of this scandal, even stated by the whistle blower themselves, was that democracy had been in some way undermined. This idea will now be examined briefly.

Using Jesper Strömbäcks four models of democracy: procedural, competitive, participatory, deliberative (2005), as reference to standards with normative implications, we can position at what levels democracy might be being disrupted. Arguably, it is towards the least publicly involved the end of the spectrum that the discussion caused by the Cambridge Analytica scandal concerns (The order of perceived public involvement being from procedural to deliberative). Here considerations will be predominantly concerned with democracy as styled within the competitive standard.

Competitive democracy

The standard of competitive democracy holds that there be proper competition and choice between political elites, enabling thorough scrutiny from an informed electorate. In this sense, ‘it is the political elites that act, whereas the citizens react’ (2005, p.334). Citizens therefore select which of the political elites they think will give them the best product, ’as in a marketplace of goods’ (2005, p.334). Strömbäck goes on to state that for this to be so, fact can fiction be disguisable along with the purposes of different kinds of media content (2005, p.334).

Personalised campaigning

Key arguments surrounding the personalisation of media can be found in the works of writers like Eli Parser (2011), and Cass Sunstein (2001). One shared theme is the erosion of a shared reality, instead replaced by polarised homogenised spaces (filter bubbles / echo chambers). Helen Nissenbaum posits that considering individualised voter targeting; an argument for could be to maintain the freedom of competition within political campaigns and an argument against is that the process of personalisation would distort decision making processes of voters (2010). At Mark Zuckerberg’s congressional hearing, US Senator Chuck Grassley made a point of stressing that campaigns from both sides of the isle have progressively made use of the latest technologies within campaigns to achieve the upper hand. This is something that is true in other countries also. Most election campaigns require candidates to debate publically on a common set of issues. Without the personalisation of all media, though the background of these issues may be distorted, there needs to be at least some shared reality for candidate’s campaigns to gain momentum amongst undecided voters. Though it is probably not ideal, one could make the case of this being within the standard of competitive democracy. This is of course if truth is still upheld, something that seems tenuous here, posing more involved epistemic questions.

Roles of different media

Between social and broadcast media, it seems apparent that there are differences in the types of issues that can be effectively communicated. Social media seem to have efficacy in communicating shared experiences less reliant on concrete facts. Contrastingly the inherent structure and elevated broadcasting ability of traditional media renders them more adept in co-ordinating and presenting more complex stories. An implication for journalism in the idea of competitive democracy is that it can act as a watchdog and hold the political elites to account (Strömbäck, J. 2005. p.341).

With the example given by this issue: The Guardian/Observer could piece together and co-ordinate actors in a considered manner. Responses made on Twitter the with #deleteFacebook established communication channels for users to share sentiments which then extended and added to the initial story. We could ask, without the social media response would there be as much pressure for the US congress or Facebook to respond. Perhaps other actors may have perused the issue, it’s hard to tell. The question here is does the current media ecosphere support of the needs and desires of citizens and have actors have been held to account. Do scandals indicate functionality beyond the exposed dysfunction? the fact there are scandals often means there are attempts to address their issues. Apologies have been made and steps have been laid down to address the issue, but Facebook has so far managed to get away without fines or punishment.

Concluding discussion

In some respects, its unconvincing that Facebooks services were used in an un-indented manner. Facebook makes money by providing tools to communicate to curated audiences. This is what Cambridge Analytica was doing. The only differences were that 1) overtly political content was used in targeting instead of commercial and 2) the data used originated from a time of different internal policies. Facebook has seen this was unsavoury and is offering ways to address the issue. Though there is bound to be more data like this out there and similar situations may happen again. The tone has been set to what users currently think is acceptable. The control and accumulation of data is the key here. This is more generalizable to the underlying logic of the web 2.0 business model. The cyclic nature of processing and archiving data performed in collaboration between users and platforms, what Robert Gehl has described as ‘affective processing’ (2011) describes their state of function. We could cite the often-referenced Tim Berners-Lee as someone calling for the re-decentralisation of the internet. Work like that done at the Open data institute is obviously needed, there is a strong case for letting users have more control over their data. This is particularly important regarding its increase use within AI, something that magnifies the inequalities of data access.

Conclusion

Considering the methodologies used in this series, First with Twitter and then the articles published by The Guardian, provided perspective on subtopics within the issue. The TSNE visualisations and word co-occurrences used with the Twitter data mapped related terms, whilst hashtag counts more concretely identified trends. Comparisons between The Guardian articles of the corresponding timeline help to offer context to other recent personal data scandals. This exploration was beneficial in establishing a starting point for more in depth discussions. Main points that have been discussed here include standards for democracy, negotiations of data and privacy and the underpinning strategies of Facebook as a platform. Though what is presented here may be incomplete in parts, it provides a research and experience that may be helpful to personal future projects.

Considering the Cambridge Analytica scandal as it has evolved has shed light on numerous cultural foundations. Issues of privacy, data and election regulations in relation to technology have been recurrent in recent history. As technologies evolve or attitudes change, renegotiations consistently need to take place for aspirations of consensus to be approached, yet arguably never attained. Research considering this may very well be important in the formations of decisions made.

References

- Bucher, T. and. Helmond, A. 2018. The Affordances of Social Media Platforms. In: Burgess, J., Marwick, A. and Poell, T. ed. The SAGE Handbook of Social Media. London: SAGE Publications. pp.233-253.

- Gehl, R. 2011. The archive and the processor: The internal logic of Web 2.0. New Media & Society [Online.] 13(8). pp.1228-1244. [Accessed 5 May 2018]. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444811401735

- Gillespie, T. 2018. regulation of and by platforms. In: Burgess, J., Marwick, A. and Poell, T. ed. The SAGE Handbook of Social Media. London: SAGE Publications. pp.254-278.

- Marwick, A. and Boyd, D. 2014. Networked privacy: How teenagers negotiate context in social media. New Media & Socitety. [Online]. 16(7). pp.1051-1067. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444814543995

- Nissenbaum, H. 2010. Privacy in Context: Technology, Policy, and the Integrity of Social Life. California: Stanford University Press.

- Tsay-Vogel, M., Shanahan, J. and. Signorielli, N. 2018. Social media cultivating perceptions of privacy: A 5-year analysis of privacy attitudes and self-disclosure behaviours among Facebook users. New Media & Society [Online]. 20(1) pp.141-161. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444816660731

- Strömbäck, J. 2005. In Search of a Standard: Four models of democracy and their normative implications for journalism. Journalism Studies. 6(3), pp. 331-345.

- Van Dijck, J. 2012. Facebook as a Tool for Producing Sociality and Connectivity. Television & New Media. [Online]. 13(2) 160–176. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1527476411415291

- Young, A. and Quan-Haase, A. 2013. Privacy protection strategies on Facebook, Information, Communication & Society. [Online]. 16(4), pp.479-500. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1369118X.2013.777757